I was watching a lecture where Simon Gikandi was speaking about African literature and the untranslatability of some terms or words in African novels. He mentioned ikenga from Things Fall Apart, and the pumpkin in Song of Lawino (in this case, it was not the word but the concept of the pumpkin and what it meant to the Acholi people).

Some things are just untranslatable and though some readers may have a teeny bias towards works with these untranslatable words, they actually give stories flavour. When a story is written in an indigenous language and is then translated into English, it may not completely lose its flavour in the sense that the sentiments, the preference of flowery language over a curt one, and the actions of the characters (prostration in a Yoruba setting) remind the readers that the novel does not belong to the English.

However, with the transfer of words from one language to the other, the tossing of terms and culture over thousands of miles, there is bound to be words that drown in that vast sea. Words that have no literal meaning in English, but have a cousin or two who can stand in for them. Cousins who try to straighten the curves and meaning of these words so that they are understood without the need to understand the background from which they come. Cousins that wash the black out of the words.

Thankfully, we have words that refuse to be translated—to be taken away from their roots and the wide context that goes centuries back in the coarse soil of their land. These words are the real MVPs. The Agbas. And you have no idea how much I love to see them in African novels.

The untranslatable.

Words that do not have a counterpart in the English language. Words that stem from a culture and cannot be understood without first understanding the culture. These words are like music to the ears and they always stand, sentinel against the complete transformation of a work of art.

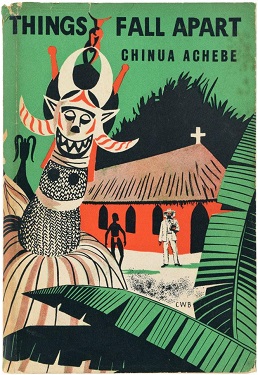

Take Ikenga in Things Fall Apart for example.

Sure, a quick Google search will produce ‘In the Igbo language, “Ikenga” translates to “place of strength” or “place of power”. It’s a sacred object and a powerful symbol representing a man’s strength, personal power, and achievements within the Igbo culture. Ikenga is typically a wooden carving, often of a human figure with ram horns, and is associated with an individual’s Chi (personal god) and their success in life.’

This was copied verbatim from Google’s Generative AI by the way.

And it explains it well enough to induce an ‘aha’ nod or two. However! How do you translate the word into English? What is an appropriate English counterpart? Idol? Wooden carving? Wooden strength? Powerful symbol?

Here’s a line from Things Fall Apart. Try to replace ikenga with any of those suggestions.

...The two pieces of his ikenga lay where their violator had kicked them in the dust…

Asides the fact that it sounds awkward, even the use of ‘Idol’, which sounds better than the rest of the phrases, gives it an entirely different meaning. It takes something away from the story that should remain in it. This is what happens when you force translations for the sake of making a story open to one and all.

The untranslatable as a ‘concept’.

Sometimes, the untranslatable is not even a word but the weight of the word—the meaning of the word to the people who understand.

Like the pumpkin in Song of Lawino whose importance is only understood by the Acholi people or through an understanding of the Acholi culture, a writer could write a piece where things get progressively horrible because of a sacrilegious act, and finally reveal that the ‘oh so sacrilegious’ act was the killing of a serpent.

Because ‘serpent’ here demands that the reader understand the importance of the serpent to the people the piece was originally written for and about, or that the writer explains this importance in detail, the ‘serpent’, though an easy enough thing to imagine, becomes untranslatable.

Now, of course, art is to be enjoyed by everyone, but I’ve learnt that you can enjoy something and not understand it. I don’t understand Yoruba but I’ve listened to Anendlessocean more than I’ve listened to any other artist this year. I am fine twisting my tongue until it pronounces the Yoruba verses well enough. A friend helped me translate some verses and though the translation was nice, it did not carry as much weight as when it was said in Yoruba.

I cannot even remember his translation, but I still hear the original verses echo in my head. And it is not a matter of ‘hyping the exotic’ like some of these things go—it is just an appreciation of the original and different.

Art is meant to be enjoyed, but not necessarily understood. Besides, what are a few untranslatable words in a novel that is, say, 90% English?

And the thing with the ‘untranslatable’ is that these words usually compensate for their untranslatability with context. If a character says ‘Dan Ubanka’ and the author doesn’t immediately translate the word with italics, the context would hint at what the term means. Maybe a fight would break out, or there would be a lashing, or someone listening would decide that the speaker is quite rude. You do not have to understand it to appreciate it.

And if you try to translate it, you might get ‘Son of your father’. Quite harmless, yes? Say that to a Nigerian northerner first.

Note that I’m not encouraging writers to use these words to confuse their readers, neither am I saying the untranslatable aim to confuse. All I am saying is that the untranslatable just cannot be directly translated to English or other languages even, and this is fine. They are part and parcel of the culture from which they stem, so rather than try to find a counterpart in another language and culture, a solution would be for the reader to understand the words from within their original culture and then let them be.

Yes. Appreciate them and leave them alone.

Besides, if you ask me, it is not an author’s responsibility to explain everything to the reader. The author shouldn’t have to bend over backwards to find corresponding English terms for their untranslatable words. The reader should learn the concept, then find the words in their own language that best help them assimilate the information.

Anyhoo, here’s the video that inspired this post. Listen carefully: Simon Gikandi speaks like Simon Gikandi and it is a manner of speech you would have to train your ears to understand (if you are too used to Nigerianese or whatever you spend your time listening to). And in a way, even this is a beautiful example of untranslatability.

For my short attention span(ners?), it is llloooonnnggg.

See you Saturday! Don’t forget to comment and share.