Childhood—such a universal and yet very individual thing. We’ve all been children, though for how long depended on circumstances unique to each of us. Childhood is usually the phase of innocence, where everything is a potential question and each day is truly a new day, but it isn’t the case for every child on earth and this portrayal may pigeonhole child protagonists into one-dimensional characters.

We’ve all been children, and we’ve probably all been around children at least once in our adult life, so let’s take a look at children in African fiction. Not the representation of, I’ve written enough representations for now, but children as protagonists and narrators.

Writing children is risky business, because while we might think we know children, we can’t say for sure we won’t lean into one of two extremes when writing them: a caricature child complete with giggles and naivety and rainbows or an adult in a child’s body complete with adult ideologies and language (think Stewie in Family Guy). Now, while Stewie’s character works perfectly for the show, chances are, most authors aren’t trying to write another Stewie but just want to write a story narrated or lived by a child.

The Big Questions.

So, are there African fiction told from the vantage points of children (when the authors themselves are no longer children) and do the authors do justice to this undertaking?

To answer these questions, let’s look at two African novels with child protagonists/narrators. Ah, there are African novels told from the POVs of children! Glory!

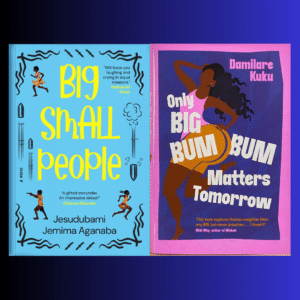

Our novels are Big Small People by Jesudubami Jemima and Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow by Damilare Kuku.

The Big, The Small, And The People

In Big Small People, Jemima introduces us to three children—Deborah, Stephanie and Ahmed—each having different backgrounds. These children, products of their environments, come to us broken, anxious and scared. Nothing like the problem-free cuteness personified humans we define as children. These qualities, and the fact that we know there are children like them everywhere—heck, some of us were these children—makes them feel authentic and well-written.

The children act like children. They misunderstand things, they tell the truth without agenda, they eavesdrop, they are naïve in the ways only children can be.

Jemima sometimes made the children use words that were at odds with their age and circumstances, but for successfully making these characters nuanced, we can forgive this oversight.

The children struggle with the voicelessness and helplessness of childhood, confusion, faith, and a growing understanding of the injustice of the world. Jemima paints a picture of childhood under pressure and the picture is clear as day.

The Big, The Bum And The… Bum?

Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow by Damilare Kuku has a number of protagonists, amongst which is Témì, the last born of the Toyebi household. Technically, at 20 years old, she isn’t a child, but she does still struggle with her childhood insecurities and the story digs into the past long enough to have us acquainted with little Témì and the space she inhabits.

At first glance, Témì’s wish for a Brazilian Butt Lift seems like a whimsical and childish one. When you look again, though, you realise that Témì’s proclamation isn’t born from a shallow desire to be desired, but is a response to years of being body-shamed and feeling inadequate in her own skin. It is from the need to be seen, not leered at, but really seen by her family. It was the culmination of years of shouting for someone to notice and accept her even as she tried to stake her claim in the world and form a foothold in her crumbling family.

Témì is confused, grieving, scared, dramatic, hopeful and most times naïve, but this is exactly why she works. She is a girl trying to navigate that space between childhood and adulthood and trying to understand what her murky feelings all mean.

My verdict? For the most part, these writers get it. They don’t write cute dolls or boss babies but instead write characters who are chaotic, contradictory, confused, self-righteous, generous and startlingly perceptive. They give us real children.

A good child narrator doesn’t tell us a story. They don’t weave the right words, teach or preach to us—at least not overtly. A good child narrator shows us a story, their hands wide open, saying ‘This is what I saw, this is how I felt, do with that what you will’.

African fiction (especially short stories and novellas) is full of child narrators, and though not every writer gets it right, some manage to write children the way they should be written—as children. Some of them go a step further to remind us that children are not blind and even though they may not understand everything, they do observe everything.

And maybe, just maybe, as a by-product, these stories are mirrors held up to our excesses that scream for us to pause and check ourselves.

Awesome 😎